As often happens, I had a moment of clarity while watching The Colbert Report the other night. Stephen’s guest for the evening was the estimable David Byrne, quirky as ever. Near the end of the interview, Stephen put forth his theory that artists like Byrne are obsessed with not falling into the singer’s famous archetype of the middle class man with the beautiful house, beautiful wife and large automobile. After a moment of reflection, Byrne admitted that he’d spent much of his life terrified of being “normal.” Man oh man, do I ever feel him on that one.

As often happens, I had a moment of clarity while watching The Colbert Report the other night. Stephen’s guest for the evening was the estimable David Byrne, quirky as ever. Near the end of the interview, Stephen put forth his theory that artists like Byrne are obsessed with not falling into the singer’s famous archetype of the middle class man with the beautiful house, beautiful wife and large automobile. After a moment of reflection, Byrne admitted that he’d spent much of his life terrified of being “normal.” Man oh man, do I ever feel him on that one.

I too am terrified of normalcy. Growing up, I had no doubt in my mind that I would be internationally beloved by the time I was 20. I was certain that I was a remarkable person, and as such, I should always strive to stand out from the crowd. Thus, I wore ridiculous clothes to school, co-founded an oddball rock band, cultivated obscure tastes in film, books and music. I did everything within my power to announce to my small town surroundings that I was Unique and Exciting. If something I enjoyed caught on with the mainstream, I renounced it immediately. The Beatles were like a religion to me in middle school, but when one of the football cheerleaders showed up at school wearing a Let It Be t-shirt during freshman year, I denied them three times before the cock crowed. Being a contrarian became a lifestyle in and of itself.

And now here I am at thirty, not yet famous and slouching steadily toward normalcy. I’m happily married and gainfully employed with a daily commute to the suburbs. I own two cats, a sensible car and, within the next few weeks, my very own house. And good gravy, does it feel weird, particularly the part about the job. I used to read Dilbert and watch Office Space and pity the poor saps who could sympathize with the characters. I was convinced that such a fate could never befall an artist and individualist like me. And yet, here I sit in my cubicle, sneaking in a clandestine blog entry in between mundane, soul-numbing work projects, and I fear myself a cog in something turning.

In that same interview, Colbert suggested that for someone like David Byrne, normal is weird. Byrne essentially agreed, saying that he’d given it a try and it hadn’t really taken. Perhaps that’s why 9-to-5 life has proven so toxic to me. For folks like David Byrne and me – and I’m going to go ahead and put the two of us in the same boat, because self-aggrandizement is one of my favorite pursuits – the mundane is the unfathomable. I’ve had a lot of weird writing jobs in my time, from crafting press releases for a children’s country music singer to playing Frisbee with Hugo the Hornet to leading a séance aimed at resurrecting the ghost of Pete Maravich. For me, none of those experiences is anywhere near as surreal as hiding behind fabric-covered walls eight hours a day while trying to come up with my three-dozenth synonym for “stretchy.”

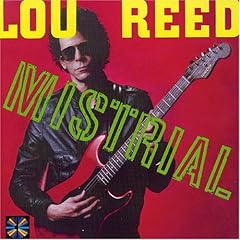

A couple of days ago, I listened to Lou Reed’s 1986 album Mistrial, one of Lou’s bigger critical failures. I don’t think it’s as bad as its reputation, but I can’t deny that it’s a really peculiar, rather difficult album for which I’m seldom in the mood. This time around I finally hit on why Mistrial just doesn’t work: this is the sound of Lou Reed trying to be normal.

Everything about Mistrial is in line with the times, from the overproduced, generic rock to the uninspired, sometimes insipid lyrics. This was the period when Lou was kicking drugs, settling down and putting his prior hedonism behind him. That stab at real-world normalcy appears to have bled through into his art, distilling a reckless, risk-taking weirdo into a second-rate Bruce Hornsby. Simply put, normal just doesn’t work on Lou Reed.

Thankfully, the last couple of decades have seen Lou getting his weird-ass groove back, recording album-length meditations on death, staging gonzo rock operas and writing 18-minute songs about feeling like a possum. Not everything has been a success, but even the failures have been interesting. That gives me hope.

Perhaps normalcy is just a necessary phase imposed upon the abnormal by age and economics. Maybe I’m just serving my short sentence in this fluorescent-humming hellscape, paying my dues because I wanna sing the blues. I take comfort in the knowledge that I still hate this as much as I did the first day I set foot in a corporate office. As long as I can keep myself from getting numb, there’s hope.

And to tell the truth, when I’m behind the wheel of my compact automobile, heading toward my beautiful house and my beautiful wife, I never ask myself, “How did I get here?” That question only arises every morning as I drive in the opposite direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment